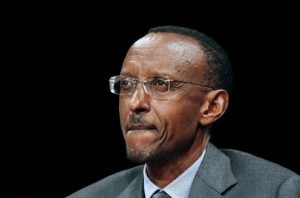

Rwandan President Paul Kagame

When the details of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide were revealed to the world, the horrifying and grizzly events of those 100 days shook the international forum. General Paul Kagame was revered as a hero for leading the Rwandan Patriotic Front to victory and ending the genocide, forcing more than 1 million Hutu refugees to flee the country. Among those refugees were approximately 50,000 Interahamwe militants who carried out the genocide, which cost the lives of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Since then Kagame has served as the de facto leader of Rwanda, obtaining close powerful allies in the United States and the United Kingdom, using their guilt for failing to respond during the genocide to gain fervent support for the Kagame regime. Kagame has utilized this powerful backing to carry out two wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as countless support operations for rebel factions in Eastern Congo, most recently illegally backing the M23 rebellion. Only in the last six months has Kagame come under scrutiny from his powerful allies for supporting ongoing rebellions in the DRC and using this as a pretext to exploit the vast mineral wealth located in that region.

Kagame has been given infinite credit for pulling Rwanda out of the ashes of the genocide and rebuilding the country. This credit is somewhat justified. However, behind the scenes is a leader and a regime that operates in a manner much closer to a criminal organization than a state. The reality of modern day Rwanda is that of a police state in which the minority Tutsi and their leader impose harsh sentences and oppression on anyone that contradicts the will of the government. Kagame has even ostracized former Tutsi allies, handing down 20 to 24-year sentences to four close cabinet members in 2011. He has also targeted the majority Hutu opposition, using the charge of denying genocide to imprison journalists and the opposition leader Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza after she questioned why the genocide memorials did not provide tributes to Hutus that died during the slaughter as well.

Now Kagame has begun to take things a step further with political assassinations. On New Year’s Day, former Rwandan Spy Chief Colonel Patrick Karegeya was found strangled in the upscale Michelangelo Towers in Johannesburg, South Africa. A bloody towel and a curtain cord were found on the scene. Karegeya was once a Kagame ally in the Rwandan government, but fell out of favor when he spoke out against Kagame’s tactics and was charged with insubordination. He was one of the four cabinet members given a lengthy sentence in 2011 in absentia. He fled to South Africa in 2007, where he was granted asylum.

This is not the first time Kagame has allegedly attempted an assassination of a former colleague. Former Rwandan Army Chief of Staff General Kayumba Nyamwasa survived three assassination attempts in 2011. During the first attack, he was shot in the stomach and the next two attacks were foiled by the South African police shortly after as he recovered from the initial onslaught. Granted, both Karegeya and Nyamwasa were accused of a coup attempt against Kagame, but attacks on other states’ sovereign soil is bold, even for the seemingly invincible Kagame.

In addition, Kagame and his cronies have been accused of a slew of assassinations and assassination attempts against journalists, former employees, doctors and priests, as well as former Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, an event that sparked the genocide. Whether or not the extent of these accusations are true (a French report has cleared Kagame of the assassination of Habyarimana), the slaying of Karegeya and the attempts against Nyamwasa are indeed alarming and point to a pattern of political assassinations designed to strike fear in the opposition and maintain the stranglehold that Kagame’s one-party system maintains.

2017 will be a very telling year for Rwanda as Kagame’s second term will come to an end. He is not permitted to seek re-election under the constitution. However, this may not deter him from changing the constitution or ushering in a successor that will report to his authority even after he leaves office. In a state where the press is run by the government and the 2010 elections saw all three of Kagame’s opponents either imprisoned or in exile, the strict dictatorial rule in Kigali shows all the signs of a continued authoritarian police state where the majority are oppressed and any competition is fervently put down. Couple this with the trend of assassinations of former Kagame confidantes and the outlook for Rwanda remains hazy.

Until the evils of the genocide can be put behind them and the country can find some semblance of harmony between ethnic groups, the nation as a whole is just one shot away from rekindling a bloody civil war that could see the horrors of the genocide resurface. For now, Kagame’s Western allies must understand that running a country with an iron fist and attacking opponents like a criminal organization is exactly the opposite of the ideals that democracy is supposed to be built upon. Rwanda cannot be considered the darling of Africa until illegal murders and financed rebellions in neighboring countries are stopped. If nothing is done, then the next Rwandan Civil War will be on the hands of those that supported this behavior.

Daniel Donovan is a writer for the Foreign Policy Association and the executive director of the African Community Advancement Initiative. You can follow him on Twitter @DanielRDonovan or @ACAinitiative.

Source:http://www.usnews.com/opinion/blogs/world-report/2014/01/10/kagames-iron-fist-could-rekindle-rwandan-civil-war?src=usn_tw