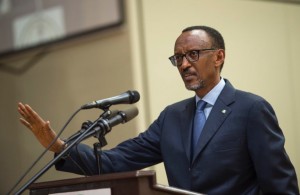

Paul Kagame is not just any other African dictator. He seems to hold the keys to modernity. He enjoys, or at least has long enjoyed, a positive aura on the international scene. He governs Rwanda, which was home to one of the most horrible nightmares known by Humanity in recent decades. Too equanimous a writer would not have been suitable to discuss such a personality, particularly in such a context. Gérard Prunier’s portrait reflects both the passion of a man who is sensitive to the dramas occurring in the area and the science of a great historian of Africa’s Great Lakes region.

Michel Duclos, Geopolitical Special Advisor, editor of this series

In the twilight of the 20th century, the Rwandan genocide of 1994 appears as the worrying token of a world that we hoped would end with the opening of another, one that would bring hope. The last century had been one of horror, but the recent fall of the “Evil Empire” seemed to symbolically close it. Yet Rwanda suddenly cast a gloomy light on this brand new optimism, which we tried to conceal with a poorly constructed historical parallel. In this small, obscure country, of which almost no one had ever heard, there had been an outbreak of “tropical Nazism”. Yet, among the two great terrors of the 20th century (Westerners never succeeded in conceiving universal history as anything other than exotic declinations of their own history, the only one that counts and marks the world’s true scansions), the two worst horrors had been Nazism and Stalinism. And here came the “filthy beast”, resurfacing in Africa and rekindling our worst memories.

The problem is that this historical parallel was not adequate. President Habyarimana was not very Hitlerian (and he had died at the time of the genocide). France was jumping up and down frantically to explain that no, this was not something it had ever wanted, and that, in any case, it hadn’t done anything. The United Nations, symbol of the post-1945 mantra “never again”, were indeed present in Rwanda, but hadn’t done anything either. Meanwhile, the African Union, i.e. the continent’s self-proclaimed conscience, was entrenched in a deafening silence. But fortunately, there was the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) – the good guys! – and their leader, who vaguely looked like some kind of warrior monk, Major Paul Kagame. What a relief. The tragedy had a hero, and the global public opinion welcomed him, finally relieved to find a savior in the midst of all this horror. But who was he really? Nobody knew. Not to mention that the general ignorance towards pre-genocide Rwanda was abyssal. The result was an unknown hero against a backdrop of African clichés.

Kagame very unconventional “military career” lasted 16 years and got him involved in some of the most extraordinary events of the century.

Paul Kagame was 36 years old at the time, and he was not really Rwandan. Having grown up in Uganda as the son of refugees since the age of four, he was a Major in the Ugandan army and a citizen of his host country. His trajectory was quite atypical for a refugee. Shortly after graduating from high school, he had joined the uprising guerrilla war in Uganda at the age of 20, as the Tanzanian army entered the country in 1978 to overthrow dictator Idi Amin Dada. His very unconventional “military career” lasted 16 years and got him involved in some of the most extraordinary events of the century.

He was profoundly shaped by this period of his life – his “Ugandan” life. Uganda in the 1970s and 1980s was a jungle dotted with corpses, where everyone betrayed everyone. The international community, which had rightly vilified Idi Amin, was walking away now that he had disappeared. It didn’t matter that dictator Milton Obote, elected in a rigged election approved by the British and Commonwealth authorities, killed more people than Idi Amin (more than 300,000 deaths between 1981 and 1986). What mattered was that, in the context of the Cold War, Obote was “a friend of the West”, even if he used North Korean artillery. In fact, this allowed Western powers to avoid getting their hands dirty in trying to keep the country together by their own means.

The West helped survivors to survive through international aid, and a division of labor that Kagame would later reproduce, first in Rwanda, and then in Congo. His contempt for the “international community”, his diplomatic cynicism and his humanitarian hypocrisy can be explained by his experience of the Ugandan civil wars between 1978 and 1986. So can his vision of the “hero”. Indeed, in January 1986, Kagame entered Kampala as a winner, alongside his leader Yoweri Museveni.That was before he saw this advocate of the extreme anti-colonialist left become, through a series of opportunist shifts, the perfect duplicate of what he had fought all his youth.

In 32 years, Museveni’s reformist power mutated into an authoritarian and corrupt State, and the former main opponent of the regime was the former head of the guerrilla’s medical services. Kagame reproduced exactly the same pattern, to the point that he now finds himself in conflict with an opposition composed by 80% of his former comrades in arms during the struggle of the 1990s (and not of ex-genocidaires as he suggests). First, of course, he served in the Ugandan regular army after the victory. Kagame, the chief’s loyal follower, became head of the army’s secret service. His profile was interesting to Museveni: Kagame was basically a foreigner, even after his years of war in Uganda. Some groups such as the Baganda or his own ethnic group, the Banyankole, constantly reminded him of this.

His contempt for the “international community”, his diplomatic cynicism and his humanitarian hypocrisy can be explained by his experience of the Ugandan civil wars between 1978 and 1986. So can his vision of the “hero”.

After all, there were only two “Rwandans” among the first 17 insurgents of 1981, the other being Fred Rwigyema, who became Chief of Staff of the Ugandan army. Two “foreigners” at the head of the country’s military establishment: what better way to prevent a coup? Kagame kept quiet, observed, learned. And he noticed the pursuit of the same humanitarian ambiguity that served Obote so well in his time. Amnesty International sent a mission to Uganda in order to criticize Museveni for his brutal treatment of imprisoned insurgents from northern ethnic groups, who supported Obote during the civil war and who continued to fight sporadically. The NGO called for the creation of a justice system able to deal with cases of detention of captives from the guerrillas. The President passed the problem on to Kagame, who was appointed President of the Armed Forces Itinerant Tribunal. He was perfect at the job, and the corpses resulting from the Tribunal’s convictions, which he brought back to Kampala, were always in excellent condition and showed no signs of abuse. The man is cold and merciless, but he is efficient and knows how to respect procedures.

In 1987, he began to extend his contacts within the Rwandan diaspora, who took advantage of his position in Uganda to set up a political military structure aiming to overthrow the Hutu regime in Kigali. However, anti-Rwandan pressure escalated in Uganda, where Museveni was forced to slowly marginalize an entire generation of refugees and their children who had supported his rise to power. After a brief hesitation, General Rwigyema, who, as a Ugandan, felt bitter and betrayed, switched sides and decided to join the RPF. For Kagame, this was a disaster: Rwigyema was very popular in the diaspora, while Kagame was not. Moreover, their two Rwandan affiliations were entirely antinomic: Rwigyema was the heir to the Banyingina royal family, while Kagame came from the Ababega clan, which overthrew and killed the King during the German colonial conquest in 1896.

The man is cold and merciless, but he is efficient and knows how to respect procedures.

A warm and friendly heir to the royal family versus the austere descendant of an usurping clan. The invasion of Rwanda that they were planning together was marked from the outset by personal and political ambiguity. Rwigyema was aware of the difficulty of having the Hutu majority accept a “liberation” led by the Tutsi minority. Even if the Habyarimana regime was a dictatorship, and even if its Hutu opponents were many. He relied on his charisma and his openness to the Hutus of the opposition to overcome the “feudal restoration” of which Habyarimana later spoke.

The RPF attacked Rwanda on 1 October 1990, and on 2 October, Fred Rwigyema, who had commanded the invasion forces, was killed by one of his own officers. The RPF will always deny the circumstances of this death, attributing it “to the fighting”. But apart from the fact that there was only one killed that day – the Commander-in-Chief – and that the given details of his death are contradictory, a worrying shadow hangs over the murder of the RPF leader. In fact, Museveni, who discreetly supported the invasion, also had Rwigyema’s two adjutants arrested and executed. Like many other episodes paving Paul Kagame’s road to power, this one will never be clarified. The war lasted four years, and burst into a genocide triggered by the assassination of President Habyarimana. The genocide was obviously planned by the most radical circles of Hutu power, but many accused Kagame of being the perpetrator of the attack. The most specific accusations came from former Tutsi members of the RPF, some of whom became active opponents of the Kagame regime. But the global impact of the genocide somewhat mesmerized the international community, which refused to think the unthinkable about the genocide’s liberator being an element of that same genocide. Yet, as Canadian General Dallaire, commander of the UN’s inactive forces, pointed out, the RPF leader did not seem overly moved by the passivity of the international community. Nor by the genocide itself. Dallaire, who was struggling with New York to get an order for intervention, felt more committed than the Rwandan. It actually seems like Kagame has never been too concerned about his fellow citizens. Among them, there were 80,000 Hutus, who were later “forgotten” in the commemorations of the genocide – which became known as “the genocide of the Tutsi”. As for the Tutsi deaths – between 700 and 800,000 – they seem to have been considered more as the “collateral damage” of the modernization process implemented later by the new post-genocidal power in Rwanda.

To realize this, one should have a conversation with members of Tutsi survivor associations, who are under no illusions regarding this issue. For Kagame, the genocide was a huge political opportunity, of which he managed to skillfully take advantage. He succeeded in exchanging a population of “indigenous” Tutsis, rooted in the complex and ambiguous Rwandan reality, for another population of diaspora Tutsi, much more educated, militarized and disciplined, who ended up being the ideal people for the RPF project.

Kagame had a plan for Rwanda. A plan similar to him: cold, efficient, entirely focused on technical success, not particular about the means employed. He managed to sell it to a relieved international public to whom he promised fundamental changes – an honest administration, security, urban cleanliness, improved transport and public health – as well as a few gadgets that always please Westerners, such as Internet access on buses or a ban on plastic bags.

Kagame, shrouded in the aura granted by his status as anti-genocidal hero, led the offensive and overthrew the old tyrant.

Protected by the genocidal shield, he knew he could practically do whatever he wanted. Moreover, he had always won in the past: escaping the fate of a stateless refugee to gain access to the highest levels of power in Uganda, taking control of the RPF, winning a second civil war in Rwanda by concealing his own violence thanks to the genocidal apocalypse, creating a government of “national unity” after the genocide, then abolishing it during a massacre committed by his own troops (Kibeho, 1995), and, finally, consolidating his absolute power thanks to election scores worthy of Stalin’s (95% in 2003, 93% in 2010 and 99% in 2017). He didn’t even need to cheat, everyone did actually vote for him. Fear was such that obedience became real. And the international community, trapped in its remorse and seduced by the progress he introduced, nodded along. He nonetheless did make a big mistake: invading Congo. It had all started so well: the surviving genocidaires, who had taken refuge just a few kilometres from the border, were constantly launching harassment raids on Rwanda, which were both unnecessary and deadly.

After two years of preparation, Kagame succeeded in gathering a coalition of African States, supported by the United States, which wanted to get rid of its old accomplice from the Cold War, Mobutu Sese Seko. Kagame, shrouded in the aura granted by his status as anti-genocidal hero, led the offensive and overthrew the old tyrant. This event was followed by President Clinton’s visit to Kigali, where the latter apologized for his country’s passive attitude during the genocide. The apology was justified, but the timing was not right. Kagame is steady-handed, but he is also extremely self-confident.

Encouraged by what he already saw as yet another success, a few months later, he took an unnecessary risk by attacking both some of his allies and the regime he had just succeeded to set up in Kinshasa. The war that ensued (1998-2002) shook the entire African continent and killed nearly three million people. At that moment, the “hero” had gone a little beyond his diplomatic comfort zone and had to leave the field. His failure even had unexpected side effects, as the international community finally dared to take a closer look at what the RPF had done since coming to power.

Kagame became President of the African Union in January 2018, which has allowed him to lecture his peers, for whom he only has limited respect.

When the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was created, public opinion tried to do so but the Attorney General, the Canadian Louise Arbour, prohibited any investigation. It is only in June 2009 that the UN Mapping Report was published…on the Congo war! It did mention the “Rwandan army”, but only in a foreign perspective. Not a word about Rwanda itself, and thus of course nothing about its leader Paul Kagame.

Fascinated by Kagame’s heroic image, it seems like the international community hasn’t read this report, which is 500 pages long and highly documented, and continues to be indulgent towards the one Professor Filip Reyntjens from the University of Antwerp calls “the greatest war criminal in power today“. Kagame’s self-confidence was boosted by the disdain the international community displayed for the truth when, for example, the Paris Public Prosecutor requested a dismissal (13 October 2018) of the case against his associates who had been involved in the attack that cost Habyarimana his life.

Kagame became President of the African Union in January 2018, which has allowed him to lecture his peers, for whom he only has limited respect. The opposition had long been disciplined through robust methods. MP Léonard Hitimana and former President of the Court of Cassation Augustin Cyiza disappeared without trace. The Vice President of the Green Party (opposition) was found dead after being tortured. The journalist Jean-Léonard Rugambage, who was investigating the case of General Kayumba Nyamwasa, who had switched to the opposition, was killed in 2010 after Kayumba himself had been the target of two assassination attempts. Former Security Chief Patrick Karegeya was found strangled in a South African hotel room on 1 January 2014. Opposition journalist Charles Ingabire, a genocide survivor, was shot dead in the street in Kampala in November 2011. And so on and so forth.

Violence has even become “democratized” since 2016, with the summary executions of dozens of petty criminals (cow thieves, smugglers, fishermen using illegal nets…) killed by the army for no other reason than to frighten people in order to “keep order”. On her recent release, Victoire Ingabire, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment for daring to run in the elections against Kagame, said: “I hope this is the beginning of the opening of the Rwandan political sphere”. Unfortunately, this seems highly unlikely.

Kagame is an iron man. Yet even iron eventually rusts away. A few years ago, he faced all the challenges with a cool temper we could qualify as “British”, but that we call “itonde” in Kinyarwanda. When Colonel Tauzin declared, while defending Gikongoro, “that he would “give no quarter” if the RPF attacked and that an officer translated (Kagame did not understand the French expression “faire de quartier”) by saying: “it means that he will kill all the wounded”, he simply observed: “It is a little hostile, isn’t it?” Today, the same man is seen shouting at his bodyguards, slapping a secretary or trampling underfoot a Minister who crossed him. Many of his former comrades from 30 years ago have joined the opposition and live in exile. He and Museveni have hated each other since the Ugandan President investigated Rwigyema’s death and today, he helps a guerrilla group that has infiltrated the Nyungwe forest and entrenched itself there. Today, Paul Kagame is the master of Rwanda, the only African head of State who can speak as an equal with the world’s great leaders, and who can influence the decisions of most international tribunals. This involves a massive and solitary power, and absolute power is absolutely solitary.

By Gérard Prunier, Historian Horn of Africa specialist

Illustration : David MARTIN for Institut Montaigne

Source: Institut Montaigne

L’opposante rwandaise Diane Rwigara, critique du président Paul Kagame, a été acquittée jeudi par un tribunal de Kigali d’incitation à l’insurrection et falsification de documents, des charges qui lui ont valu d’être emprisonnée pendant plus d’un an et dénoncées comme politiques par l’intéressée.

L’opposante rwandaise Diane Rwigara, critique du président Paul Kagame, a été acquittée jeudi par un tribunal de Kigali d’incitation à l’insurrection et falsification de documents, des charges qui lui ont valu d’être emprisonnée pendant plus d’un an et dénoncées comme politiques par l’intéressée.