Between April and July 1994, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were murdered in the most rapid genocide ever recorded. The killers used simple tools – machetes, clubs and other blunt objects, or herded people into buildings and set them aflame with kerosene. Most of the victims were of minority Tutsi ethnicity; most of the killers belonged to the majority Hutus.

Between April and July 1994, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were murdered in the most rapid genocide ever recorded. The killers used simple tools – machetes, clubs and other blunt objects, or herded people into buildings and set them aflame with kerosene. Most of the victims were of minority Tutsi ethnicity; most of the killers belonged to the majority Hutus.

The Rwanda genocide has been compared to the Nazi Holocaust in its surreal brutality. But there is a fundamental difference between these two atrocities. No Jewish army posed a threat to Germany. Hitler targeted the Jews and other weak groups solely because of his own demented beliefs and the prevailing prejudices of the time. The Rwandan Hutu génocidaires, as the people who killed during the genocide were known, were also motivated by irrational beliefs and prejudices, but the powder keg contained another important ingredient: terror. Three and a half years before the genocide, a rebel army of mainly Rwandan Tutsi exiles known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front, or RPF, had invaded Rwanda and set up camps in the northern mountains. They had been armed and trained by neighbouring Uganda, which continued to supply them throughout the ensuing civil war, in violation of the UN charter, Organisation of African Unity rules, various Rwandan ceasefire and peace agreements, and the repeated promises of the Ugandan president, Yoweri Museveni.

During this period, officials at the US embassy in Kampala knew that weapons were crossing the border, and the CIA knew that the rebels’ growing military strength was escalating ethnic tensions within Rwanda to such a degree that hundreds of thousands of Rwandans might die in widespread ethnic violence. However, Washington not only ignored Uganda’s assistance to the Rwandan rebels, it also ramped up military and development aid to Museveni and then hailed him as a peacemaker once the genocide was underway.

The hatred the Hutu génocidaires unleashed represents the worst that human beings are capable of, but in considering what led to this disaster, it is important to bear in mind that the violence was not spontaneous. It emerged from a century or more of injustice and brutality on both sides, and although the génocidaires struck back against innocents, they were provoked by heavily armed rebels supplied by Uganda, while the US looked on.

The RPF rebel army represented Tutsi refugees who had fled their country in the early 1960s. For centuries before that, they had formed an elite minority caste in Rwanda. In a system continued under Belgian colonialism, they treated the Hutu peasants like serfs, forcing them to work on their land and sometimes beating them like donkeys. Hutu anger simmered until shortly before independence in 1962, then exploded in brutal pogroms against the Tutsi, hundreds of thousands of whom fled to neighbouring countries.

In Uganda, a new generation of Tutsi refugees grew up, but they soon became embroiled in the lethal politics of their adoptive country. Some formed alliances with Ugandan Tutsis and the closely related Hima – Museveni’s tribe – many of whom were opposition supporters and therefore seen as enemies by then-president Milton Obote, who ruled Uganda in the 1960s and again in the early 1980s.

After Idi Amin overthrew Obote in 1971, many Rwandan Tutsis moved out of the border refugee camps. Some tended the cattle of wealthy Ugandans; others acquired property and began farming; some married into Ugandan families; and a small number joined the State Research Bureau, Amin’s dreaded security apparatus, which inflicted terror on Ugandans. When Obote returned to power in the 1980s, he stripped the Rwandan Tutsis of their civil rights and ordered them into the refugee camps or back over the border into Rwanda, where they were not welcomed by the Hutu-dominated government. Those who refused to go were assaulted, raped and killed and their houses were destroyed.

In response to Obote’s abuses, more and more Rwandan refugees joined the National Resistance Army, an anti-Obote rebel group founded by Museveni in 1981. When Museveni’s rebels took power in 1986, a quarter of them were Rwandan Tutsi refugees, and Museveni granted them high ranks in Uganda’s new army.

Museveni’s promotion of the Rwandan refugees within the army generated not only resentment within Uganda, but terror within Rwanda where the majority Hutus had long feared an onslaught from Tutsi refugees. In 1972, some 75,000 educated Hutus – just about anyone who could read – had been massacred in Tutsi-ruled Burundi, a small country neighbouring Rwanda with a similar ethnic makeup. During the 1960s, Uganda’s Tutsi refugees had launched occasional armed strikes across the border, but Rwanda’s army easily fought them off. Each attack sparked reprisals against those Tutsis who remained inside Rwanda – many of whom were rounded up, tortured and killed – on mere suspicion of being supporters of the refugee fighters. By the late 1980s, a new generation of refugees, with training and weapons supplied by Museveni’s Uganda, represented a potentially far greater threat. According to the historian André Guichaoua, anger and fear hung over every bar-room altercation, every office dispute and every church sermon.

By the time Museveni took power, the plight of the Tutsi refugees had come to the attention of the west, which began pressuring Rwanda’s government to allow them to return. At first, Rwanda’s president, Juvénal Habyarimana, refused, protesting that Rwanda was among the most densely populated countries in the world, and its people, dependent upon peasant agriculture, needed land to survive. The population had grown since the refugees left, and Rwanda was now full, Habyarimana claimed.

Although he did not say so publicly, overpopulation almost certainly was not Habyarimana’s major concern. He knew the refugees’ leaders were not just interested in a few plots of land and some hoes. The RPF’s professed aim was refugee rights, but its true aim was an open secret throughout the Great Lakes region of Africa: to overthrow Habyarimana’s government and take over Rwanda by force. Museveni had even informed the Rwandan president that the Tutsi exiles might invade, and Habyarimana had also told US state department officials that he feared an invasion from Uganda.

One afternoon in early 1988 when the news was slow, Kiwanuka Lawrence Nsereko, a journalist with the Citizen, an independent Ugandan newspaper, stopped by to see an old friend at the ministry of transport in downtown Kampala. Two senior army officers, whom Lawrence knew, happened to be in the waiting room when he arrived. Like many of Museveni’s officers, they were Rwandan Tutsi refugees. After some polite preliminaries, Lawrence asked the men what they were doing there.

“We want some of our people to be in Rwanda,” one of them replied. Lawrence shuddered. He had grown up among Hutus who had fled Tutsi oppression in Rwanda before independence in 1962, as well as Tutsis who had fled the Hutu-led pogroms that followed it. Lawrence’s childhood catechist had been a Tutsi; the Hutus who worked in his family’s gardens wouldn’t attend his lessons. Instead, they swapped fantastic tales about how Tutsis once used their Hutu slaves as spittoons, expectorating into their mouths, instead of on the ground.

The officers went in to speak to the transport official first, and when Lawrence’s turn came, he asked his friend what had transpired. The official was elated. The Rwandans had come to express their support for a new open borders programme, he said. Soon Rwandans living in Uganda would be allowed to cross over and visit their relatives without a visa. This would help solve the vexing refugee issue, he explained.

Lawrence was less sanguine. He suspected the Rwandans might use the open borders programme to conduct surveillance for an invasion, or even carry out attacks inside Rwanda. A few days later, he dropped in on a Rwandan Tutsi colonel in Uganda’s army, named Stephen Ndugute.

“We are going back to Rwanda,” the colonel said. (When the RPF eventually took over Rwanda in 1994, Ndugute would be second in command.)

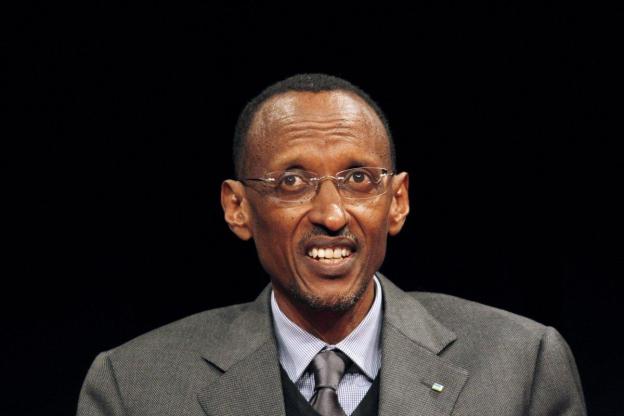

Many Ugandans were eager to see Museveni’s Rwandan officers depart. They were not only occupying senior army positions many Ugandans felt should be held by Ugandans, but some were also notorious for their brutality. Paul Kagame, who went on to lead the RPF takeover of Rwanda and has ruled Rwanda since the genocide, was acting chief of military intelligence, in whose headquarters Lawrence himself had been tortured. In northern and eastern Uganda, where a harsh counterinsurgency campaign was underway, some of the army’s worst abuses had been committed by Rwandan Tutsi officers. In 1989, for example, soldiers under the command of Chris Bunyenyezi, also an RPF leader, herded scores of suspected rebels in the village of Mukura into an empty railway wagon with no ventilation, locked the doors and allowed them to die of suffocation.

Lawrence had little doubt that if war broke out in Rwanda, it was going to be “very, very bloody”, he told me. He decided to alert Rwanda’s president. Habyarimana agreed to meet him during a state visit to Tanzania. At a hotel in Dar es Salaam, the 20-year-old journalist warned the Rwandan leader about the dangers of the open border programme. “Don’t worry,” Lawrence says Habyarimana told him. “Museveni is my friend and would never allow the RPF to invade.”

Habyarimana was bluffing. The open border programme was actually part of his own ruthless counter-strategy. Every person inside Rwanda visited by a Tutsi refugee would be followed by state agents and automatically branded an RPF sympathiser; many were arrested, tortured, and killed by Rwandan government operatives. The Tutsis inside Rwanda thus became pawns in a power struggle between the RPF exiles and Habyarimana’s government. Five years later, they would be crushed altogether in one of the worst genocides ever recorded.

On the morning of 1 October 1990, thousands of RPF fighters gathered in a football stadium in western Uganda about 20 miles from the Rwandan border. Some were Rwandan Tutsi deserters from Uganda’s army; others were volunteers from the refugee camps. Two nearby hospitals were readied for casualties. When locals asked what was going on, Fred Rwigyema, who was both a Ugandan army commander and the leader of the RPF, said they were preparing for Uganda’s upcoming Independence Day celebrations, but some excited rebels let the true purpose of their mission leak out. They crossed into Rwanda that afternoon. The Rwandan army, with help from French and Zairean commandos, stopped their advance and the rebels retreated back into Uganda. A short time later, they invaded again and eventually established bases in northern Rwanda’s Virunga mountains.

Presidents Museveni and Habyarimana were attending a Unicef conference in New York at the time. They were staying in the same hotel and Museveni rang Habyarimana’s room at 5am to say he had just learned that 14 of his Rwandan Tutsi officers had deserted and crossed into Rwanda. “I would like to make it very clear,” the Ugandan president reportedly said, “that we did not know about the desertion of these boys” – meaning the Rwandans, not 14, but thousands of whom had just invaded Habyarimana’s country – “nor do we support it.”

In Washington a few days later, Museveni told the State Department’s Africa chief, Herman Cohen, that he would court martial the Rwandan deserters if they attempted to cross back into Uganda. But a few days after that, he quietly requested France and Belgium not to assist the Rwandan government in repelling the invasion. Cohen writes that he now believes that Museveni must have been feigning shock, when he knew what was going on all along.

When Museveni returned to Uganda, Robert Gribbin, then deputy chief of mission at the US embassy in Kampala, had some “stiff talking points” for him. Stop the invasion at once, the American said, and ensure no support flowed to the RPF from Uganda.

Museveni had already issued a statement promising to seal all Uganda–Rwanda border crossings, provide no assistance to the RPF and arrest any rebels who tried to return to Uganda. But he proceeded to do none of those things and the Americans appear to have made no objection.

When the RPF launched its invasion, Kagame, then a senior officer in both the Ugandan army and the RPF, was in Kansas at the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, studying field tactics and psyops, propaganda techniques to win hearts and minds. But after four RPF commanders were killed, he told his American instructors that he was dropping out to join the Rwandan invasion. The Americans apparently supported this decision and Kagame flew into Entebbe airport, travelled to the Rwandan border by road, and crossed over to take command of the rebels.

For the next three and a half years, the Ugandan army continued to supply Kagame’s fighters with provisions and weapons, and allow his soldiers free passage back and forth across the border. In 1991, Habyarimana accused Museveni of allowing the RPF to attack Rwanda from protected bases on Ugandan territory. When a Ugandan journalist published an article in the government-owned New Vision newspaper revealing the existence of these bases, Museveni threatened to charge the journalist and his editor with sedition. The entire border area was cordoned off. Even a French and Italian military inspection team was denied access.

In October 1993, the UN security council authorised a peacekeeping force to ensure no weapons crossed the border. The peacekeepers’ commander, Canadian Lt-Gen Roméo Dallaire, spent most of his time inside Rwanda, but he also visited the Ugandan border town of Kabale, where an officer told him that his inspectors would have to provide the Ugandan army with 12 hours’ notice so that escorts could be arranged to accompany them on their border patrols. Dallaire protested: the element of surprise is crucial for such monitoring missions. But the Ugandans insisted and eventually, Dallaire, who was much more concerned about developments inside Rwanda, gave up.

The border was a sieve anyway, as Dallaire later wrote. There were five official crossing sites and countless unmapped mountain trails. It was impossible to monitor. Dallaire had also heard that an arsenal in Mbarara, a Ugandan town about 80 miles from the Rwanda border, was being used to supply the RPF. The Ugandans refused to allow Dallaire’s peacekeepers to inspect that. In 2004, Dallaire told a US congressional hearing that Museveni had laughed in his face when they met at a gathering to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the genocide. “I remember that UN mission on the border,” Museveni reportedly told him. “We manoeuvred ways to get around it, and of course we did support the [RPF].”

US officials knew that Museveni was not honouring his promise to court martial RPF leaders. The US was monitoring Ugandan weapons shipments to the RPF in 1992, but instead of punishing Museveni, western donors including the US doubled aid to his government and allowed his defence spending to balloon to 48% of Uganda’s budget, compared with 13% for education and 5% for health, even as Aids was ravaging the country. In 1991, Uganda purchased 10 times more US weapons than in the preceding 40 years combined.

The 1990 Rwanda invasion, and the US’s tacit support for it, is all the more disturbing because in the months before it occurred, Habyarimana had acceded to many of the international community’s demands, including for the return of refugees and a multiparty democratic system. So it wasn’t clear what the RPF was fighting for. Certainly, negotiations over refugee repatriation would have dragged on and might not have been resolved to the RPF’s satisfaction, or at all. But negotiations appear to have been abandoned abruptly in favour of war.

At least one American was concerned about this. The US ambassador to Rwanda, Robert Flaten, saw with his own eyes that the RPF invasion had caused terror in Rwanda. After the invasion, hundreds of thousands of mostly Hutu villagers fled RPF-held areas, saying they had seen abductions and killings. Flaten urged the George HW Bush’s administration to impose sanctions on Uganda, as it had on Iraq after the Kuwait invasion earlier that year. But unlike Saddam Hussein, who was routed from Kuwait, Museveni received only Gribbin’s “stiff questions” about the RPF’s invasion of Rwanda.

“In short,” Gribbin writes, “we said that the cat was out of the bag, and neither the United States nor Uganda was going to rebag it.” Sanctioning Museveni might have harmed US interests in Uganda, he explains. “We sought a stable nation after years of violence and uncertainty. We encouraged nascent democratic initiatives. We supported a full range of economic reforms.” But the US was not fostering nascent democratic initiatives inside Uganda. While pressuring other countries, including Rwanda, to open up political space, Uganda’s donors were allowing Museveni to ban political party activity, arrest journalists and editors, and conduct brutal counterinsurgency operations in which civilians were tortured and killed. And far from seeking stability, the US, by allowing Uganda to arm the RPF, was setting the stage for what would turn out to be the worst outbreak of violence ever recorded on the African continent. Years later, Cohen expressed regret for failing to pressure Uganda to stop supporting the RPF, but by then it was far too late.

For Habyarimana and his circle of Hutu elites, the RPF invasion seemed to have a silver lining, at least at first. At the time, Hutu/Tutsi relations inside Rwanda had improved. Habyarimana had sought reconciliation with the Tutsis still living in Rwanda by reserving civil service jobs and university places for them in proportion to their share of the population. This programme was modestly successful, and the greatest tensions in the country now lay along class, not ethnic, lines. A tiny educated Hutu clique linked to Habyarimana’s family who called themselves évolués –the evolved ones – was living off the labour of millions of impoverished rural Hutus, whom they exploited just as brutally as the Tutsi overlords of bygone days.

The évolués subjected the peasants to forced labour and fattened themselves on World Bank “anti-poverty” projects that provided jobs and other perks for their own group, but did little to alleviate poverty. International aid donors had pressured Habyarimana to allow opposition political parties to operate, and many new ones had sprung up. Hutus and Tutsis were increasingly united in criticising Habyarimana’s autocratic behaviour and nepotism, and the vast economic inequalities in the country.

When Rwanda’s ethnic bonfires roared back to life in the days after the RPF invasion, Habyarimana and his circle seem to have sensed a political opportunity: now they could distract the disaffected Hutu masses from their own abuses by reawakening fears of the “demon Tutsis”, who would soon become convenient scapegoats to divert attention from profound socioeconomic injustices.

Shortly after the invasion, all Tutsis – whether RPF supporters or not – became targets of a vicious propaganda campaign that would bear hideous fruit in April 1994. Chauvinist Hutu newspapers, magazines and radio programmes began reminding Hutu audiences that they were the original occupants of the Great Lakes region and that Tutsis were Nilotics – supposedly warlike pastoralists from Ethiopia who had conquered and enslaved them in the 17th century. The RPF invasion was nothing more than a plot by Museveni, Kagame and their Tutsi co-conspirators to re-establish this evil Nilotic empire. Cartoons of Tutsis killing Hutus began appearing in magazines, along with warnings that all Tutsis were RPF spies bent on dragging the country back to the days when the Tutsi queen supposedly rose from her seat supported by swords driven between the shoulders of Hutu children. In December 1993, a picture of a machete appeared on the front page of a Hutu publication under the headline “What to do about the Tutsis?”

Habyarimana knew that the RPF, thanks to Ugandan backing, was better armed, trained and disciplined than his own army. Under immense international pressure, he had agreed in August 1993 to grant the RPF seats in a transitional government and nearly half of all posts in the army. Even Tutsis inside Rwanda were against giving the RPF so much power because they knew it could provoke the angry, fearful Hutus even more, and they were right. As Habyarimana’s increasingly weak government reluctantly acceded to the RPF’s demands for power, Hutu extremist mayors and other local officials began stockpiling rifles, and government-linked anti-Tutsi militia groups began distributing machetes and kerosene to prospective génocidaires. In January 1994, four months before the genocide, the CIA predicted that if tensions were not somehow defused, hundreds of thousands of people would die in ethnic violence. The powder keg awaited a spark to set it off.

That spark arrived at about 8pm on 6 April 1994, when rockets fired from positions close to Kigali airport shot down Habyarimana’s plane as it was preparing to land. The next morning, frantic Hutu militia groups, convinced that the Nilotic apocalypse was at hand, launched a ferocious attack against their Tutsi neighbours.

Few subjects are more polarising than the modern history of Rwanda. Questions such as “Has the RPF committed human rights abuses?” or “Who shot down President Habyarimana’s plane?” have been known to trigger riots at academic conferences. The Rwandan government bans and expels critical scholars from the country, labelling them “enemies of Rwanda” and “genocide deniers”, and Kagame has stated that he doesn’t think that “anyone in the media, UN [or] human rights organisations has any moral right whatsoever to level any accusations against me or Rwanda”.

Be that as it may, several lines of evidence suggest that the RPF was responsible for the downing of Habyarimana’s plane. The missiles used were Russian-made SA-16s. The Rwandan army was not known to possess these weapons, but the RPF had them at least since May 1991. Two SA-16 single-use launchers were also found in a valley near Masaka Hill, an area within range of the airport that was accessible to the RPF. According to the Russian military prosecutor’s office, the launchers had been sold to Uganda by the USSR in 1987.

Since 1997, five additional investigations of the crash have been carried out, including one by a UN-appointed team, and one each by French and Spanish judges working independently. These three concluded that the RPF was probably responsible. Two Rwandan government investigations conversely concluded that Hutu elites and members of Habyarimana’s own army were responsible.

A 2012 report on the crash commissioned by two French judges supposedly exonerated the RPF. But this report, although widely publicised as definitive, actually was not. The authors used ballistic and acoustic evidence to argue that the missiles were probably fired by the Rwandan army from Kanombe military barracks. But they admit that their technical findings could not exclude the possibility that the missiles were fired from Masaka Hill, where the launchers were found. The report also fails to explain how the Rwandan army, which was not known to possess SA-16s, could have shot down the plane using them.

Soon after the plane crash, the génocidaires began their attack against the Tutsis, and the RPF began advancing. But the rebels’ troop movements suggested that their primary priority was conquering the country, not saving Tutsi civilians. Rather than heading south, where most of the killings were taking place, the RPF circled around Kigali. By the time it reached the capital weeks later, most of the Tutsis there were dead.

When the UN peacekeeper Dallaire met RPF commander Kagame during the genocide, he asked about the delay. “He knew full well that every day of fighting on the periphery meant certain death for Tutsis still behind [Rwanda government forces] lines,” Dallaire wrote in Shake Hands With the Devil. “[Kagame] ignored the implications of my question.”

In the years that followed, Bill Clinton apologised numerous times for the US’s inaction during the genocide. “If we’d gone in sooner, I believe we could have saved at least a third of the lives that were lost,” he told journalist Tania Bryer in 2013. Instead, Europeans and Americans extracted their own citizens and the UN peacekeepers quietly withdrew. But Dallaire indicates that Kagame would have rejected Clinton’s help in any case. “The international community is looking at sending an intervention force on humanitarian grounds,” Kagame told Dallaire. “But for what reason? If an intervention force is sent to Rwanda, we,” – meaning the RPF – “will fight it.”

As the RPF advanced, Hutu refugees fled into neighbouring countries. In late April, television stations around the world broadcast images of thousands upon thousands of them crossing the Rusumo Bridge from Rwanda into Tanzania, as the bloated corpses of Rwandans floated down the Kagera river beneath them. Most viewers assumed that all the corpses were Tutsis killed by Hutu génocidaires. But the river drains mainly from areas then held by the RPF, and Mark Prutsalis, a UN official working in the Tanzanian refugee camps, maintains that at least some of the bodies were probably Hutu victims of reprisal killings by the RPF. One refugee after another told him that RPF soldiers had gone house to house in Hutu areas, dragging people out, tying them up and throwing them in the river. The UN estimated later that the RPF killed some 10,000 civilians each month during the genocide.

Lawrence Nsereko was among the journalists on the Rusumo Bridge that day and as the bodies floated by, he noticed something strange. The upper arms of some of them had been tied with ropes behind their backs. In Uganda, this method of restraint is known as the “three-piece tie”; it puts extreme pressure on the breastbone, causing searing pain, and may result in gangrene. Amnesty International had recently highlighted it as a signature torture method of Museveni’s army, and Lawrence wondered whether the RPF had learned this technique from their Ugandan patrons.

In June 1994, while the slaughter in Rwanda was still underway, Museveni travelled to Minneapolis, where he received a Hubert H Humphrey public service medal and honorary doctorate from the University of Minnesota. The dean, a former World Bank official, praised Museveni for ending human rights abuses in Uganda and preparing his country for multiparty democracy. Western journalists and academics showered Museveni with praise. “Uganda [is] one of the few flickers of hope for the future of black Africa,” wrote one. The New York Times compared the Ugandan leader to Nelson Mandela, and Time magazine hailed him as a “herdsman and philosopher” and “central Africa’s intellectual compass.”

Museveni also visited Washington on that trip, where he met with Clinton and his national security adviser, Anthony Lake. I could find no record of what the men discussed, but I can imagine the Americans lamenting the tragedy in Rwanda, and the Ugandan explaining that this disaster only confirmed his long-held theory that Africans were too attached to clan loyalties for multiparty democracy. The continent’s ignorant peasants belonged under the control of autocrats like himself.

Helen C Epstein

This is an adapted extract from Another Fine Mess: America, Uganda and the War on Terror, published by Columbia Global Reports. To order a copy for £9.34, go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

The danger of an unchallenged myth: The lie that is Rwandan President Paul Kagame

The danger of an unchallenged myth: The lie that is Rwandan President Paul Kagame

Between April and July 1994, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were murdered in the most rapid genocide ever recorded. The killers used simple tools – machetes, clubs and other blunt objects, or herded people into buildings and set them aflame with kerosene. Most of the victims were of minority Tutsi ethnicity; most of the killers belonged to the majority Hutus.

Between April and July 1994, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were murdered in the most rapid genocide ever recorded. The killers used simple tools – machetes, clubs and other blunt objects, or herded people into buildings and set them aflame with kerosene. Most of the victims were of minority Tutsi ethnicity; most of the killers belonged to the majority Hutus.